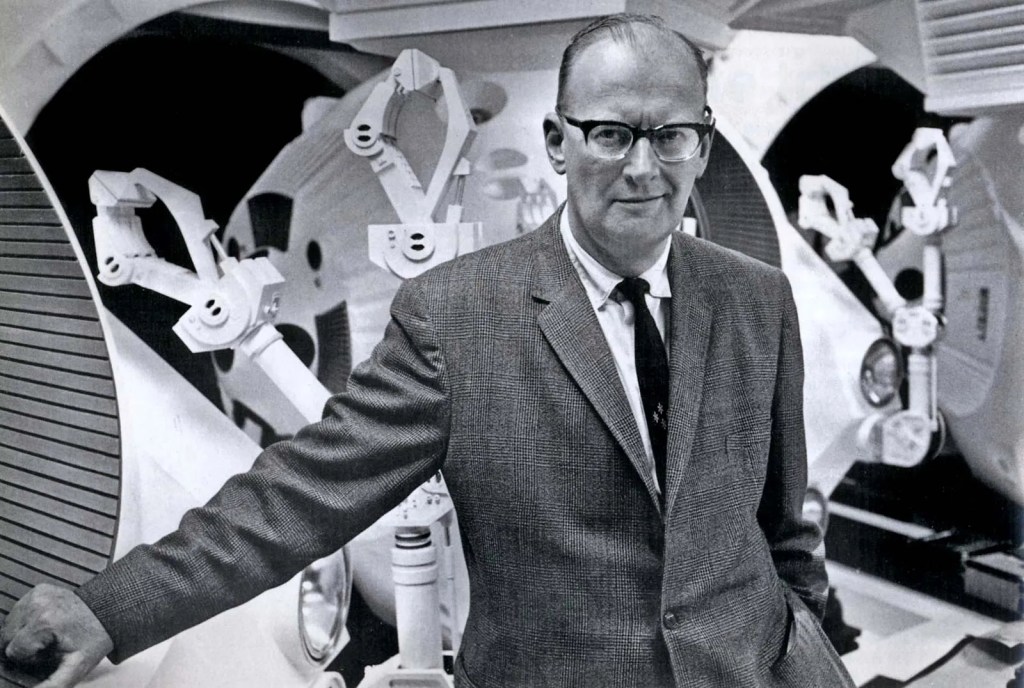

Two years ago today, the last living member of science fiction’s “Big Three” died. It was Arthur C. Clarke, whose prose was never what anyone else would call masterful, but it was sufficient. That wasn’t the point. He was an ideas man and his imagination was both awe-inspiring and troubling, grounded and mystical.

Clarke often had science on his side—real science—which is why I believe that science fiction is important. Consider how many real-life scientists say they were initially inspired by books, TV shows, etc. The inventor of the cell phone was inspired by the communicators on Star Trek, Paul Krugman became the world’s most famous economist after reading Asimov’s Foundation, and Robert Goddard, the inventor of the world’s first liquid-fueled rocket, cited The War of the Worlds as his inspiration.

Rendezvous with Rama

Rendezvous with Rama, which won both the Hugo and the Nebula, was equal parts haunting and mysterious. It’s primarily an adventure story told without the prerequisite heroes and damsels in distress (the main character isn’t just married, he’s got two wives which is, uh, apparently a thing space travelers like to do in the future), yet it’s every bit as entertaining as, say, Jack Vance’s Planet of Adventure. Science is often the cause of the characters’ dilemma, such as when they realize the weather inside the alien spacecraft will turn dangerous as it approaches the sun, but in Clarke’s world, science is usually the solution to the problems as well.

Clarke’s seminal work begins: “Sooner or later, it was bound to happen.”

On September 11th, 2077, a meteorite strikes Earth and kills six hundred thousand people. This plot point is foreshadowed by Clarke’s narration of real-life events: in June of 1908, he writes:

Moscow escaped destruction by three hours and four thousand kilometers—a margin invisibly small by the standards of the universe. On February 12, 1947, another Russian city had a still narrower escape, when the second great meteorite of the twentieth century detonated less than four hundred kilometers from Vladivostok, with an explosion rivaling that of the newly invented uranium bomb.

And about the fictional meteorite of 2077:

Somewhere above Austria it began to disintegrate, producing a series of concussions so violent that more than a million people had their hearing permanently damaged. They were the lucky ones.

The incident spurs the creation of SPACEGUARD, a program to ward against such catastrophic collisions. Fifty years later, SPACEGUARD discovers what scientists will soon call Rama: an enormous cylindrical spacecraft which has mysteriously entered the solar system and will soon leave. This gives humans a small window to study the alien craft. I was instantly hooked and spent a very long night inhaling the novel beneath my covers with a flashlight.

Rendezvous introduced me to conceptual physics. Rama, constantly spinning about its axis, generates the illusion of gravity for its occupants via centripetal force. Inside, separating the two halves of the cylindrical craft is an ocean in the form of an equatorial band. Perhaps I struggled with this imagery at first: a giant band of water that “sticks” to the inside of the cylinder’s continuous wall. When the characters ride a boat in the middle of this ocean, they can look up and see more of the ocean ahead and above them.

Sure, this type of setup has been a staple of science fiction many times before and since, but it was likely my first brush with the concept. In an interesting subplot somewhere in the middle of the book, the explorers want to get a look at the device at the far end of the craft, which they assume is some sort of a space drive. You see spaceships in movies that don’t have any visible means of propulsion all the time, but in an Arthur C. Clarke story, this is particularly curious because it violates Netwon’s third law of motion.

2001: A Space Odyssey

Some time after inhaling the entire Rama series (only the first one is essential), I found the book version of 2001, which was more or less written concurrently with the film’s production. It expanded on the Dawn of Man stuff seen in the opening of the film, which was perhaps the first time I considered human evolution and our prehistoric ancestors. The novel also expands on how Hal 9000 tries to kill the main character, which in some ways is scarier than the movie. The sequence as designed by Clarke was probably too expensive for Kubrick’s budget.

The Early Stuff

Some of Clarke’s earlier works may seem lackluster compared to mainstream classics like 2001 and Rama, but the science is still fairly hard and the stories are charming if nothing else. Some of the things he dwells on is now common knowledge for SF fans (we don’t need to be frequently reminded “There’s no up or down in space”), but I think it’s interesting to note he was writing this stuff before humans ever went to space.

An excerpt from Islands in the Sky, a novel aimed at teenagers in which the narrator wins a trip to space:

There were also, I’d discovered, some interesting tricks and practical jokes that could be played in space. One of the best involved nothing more complicated than an ordinary match.

What happens is the other astronauts play a prank on the boy: they tell him the way you make sure you have a fresh supply of oxygen is the same way miners do it back on Earth: you light a match. (Never mind why astronauts have matches on board.) If the match goes out, “well, you go out too, as quickly as you can!”

One of the astronauts demonstrates by lighting a match which promptly extinguishes itself, much to the boy’s dismay.

It’s funny how the mind works, for up to that moment I’d been breathing comfortably, yet now I seemed to be suffocating.

The narrator panics before he realizes that, in the absence of gravity, smoke has nowhere to go and suffocates the flame.

Childhood’s End

Childhood’s End is possibly the most loved of Clarke’s earlier novels. At one point in the story, the characters successfully use a device that’s essentially a spirit board, which is disappointing to those who love Clarke’s hard science. Beyond the detailed explanations of time dilation at relativistic speeds (possibly the first time I was introduced to that concept), the only thing about Childhood’s End that really sticks out in my mind is the introduction included in my edition (1990, Pan Books LTD.). There, Clarke admits that he was impressed by evidence for the paranormal when he wrote Childhood’s End, which would not hold true later in his life.

When Childhood’s End first appeared, many readers were baffled by a statement after the title page to the effect that “The opinions expressed in this book are not those of the author.”

This was not entirely facetious; I had just published The Exploration of Space, and painted an optimistic picture of our future expansion into the Universe. Now I had written a book which said, “The stars are not for Man,” and I did not want anyone to think I had suddenly recanted.

Today, I would like to change the target of that disclaimer to cover 99 percent of the “paranormal” (it can’t all be nonsense) and 100 percent of UFO “encounters.”

At any rate, I just thought I’d use this anniversary of Clarke’s death to geek out about him.