“If I tell the world that a right-wing, fascist way of doing things doesn’t work, no one will listen to me. So I’m going to make a perfect fascist world: everyone is beautiful, everything is shiny, everything has big guns and fancy ships, but it’s only good for killing fucking bugs!” — Paul Verhoeven

At first glance, the cast looked like it belonged in a television drama for teenagers. The jingoistic satire didn’t translate well to newspaper ads and 30-second TV spots. The goofy marketing made it look like a straight-to-video movie had somehow wormed its way into a theatrical release. And yet, I still went to see Starship Troopers on opening night, shuffling into the theater with the lowest of expectations. There were maybe six other people there including, I think, a local film critic who occasionally shone a penlight on his notes and impatiently touched the illumination dial on his wristwatch.

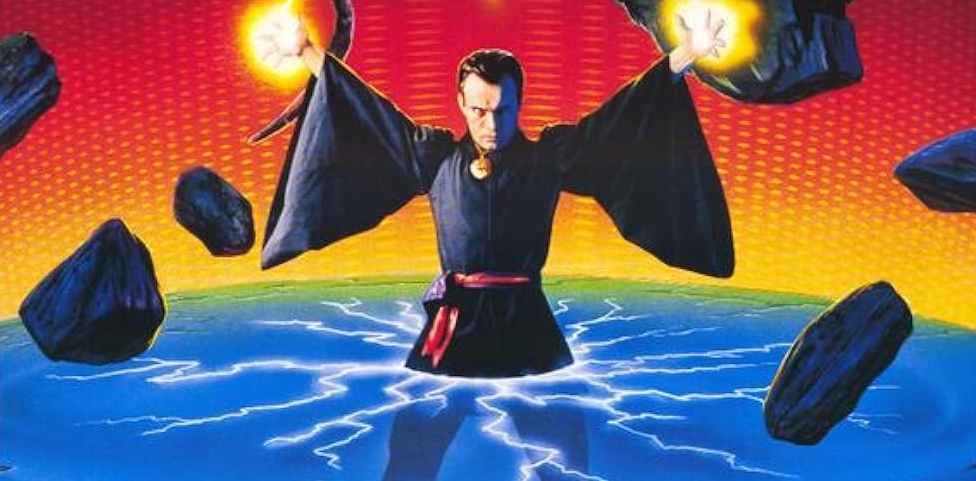

In Paul Verhoeven’s Robocop, the narrative is frequently interrupted by satirical advertisements and news segments, as if the film has commercial breaks baked right into it. Likewise, Starship Troopers opens with over-the-top war propaganda, simultaneously establishing its irreverent attitude and the premise: in the future, humans really hate bugs: the arachnid alien combatants who’ve thrown a wrench in humanity’s plan to colonize every nook and cranny of the galaxy. In fact, humans hate bugs so much that young men and women everywhere can’t wait to give up everything and fight the bastards.

Enter Johnny Rico (Casper Van Dien) and his dimwitted high school friends. Amusingly, the first act plays like a futuristic teenybopper drama before jerking the rug out from under the heroes’ feet. Rico has a hot girlfriend (Denise Richards), a hunky rival (Patrick Muldoon), a dangerously flirty gal pal named Dizzy (Dina Meyer), and an ultra-nerdy best friend played by Neil Patrick Harris, whose appearance in an R-rated romp was mildly scandalous at the time (Verhoeven had employed similar stunt casting with Elizabeth Berkley in his trash-masterpiece Showgirls, two years prior).

Rico’s girlfriend is sent to the space navy, his brainy best friend gets absorbed by the military’s science sector, and Rico ends up in the most elite squad of ground troops in existence. His drill sergeant is played by Clancy Brown, who always takes genre projects seriously and the same can be said of Michael Ironside (Total Recall’s Richter), who plays the lieutenant of Rico’s group. There Rico makes new friends for the first time in his adult life, including Jake Busey, whose maniacal appearance instantly washes away the Dawson’s Creek vibe from the earlier portion of the picture.

Just when Rico’s finally begins to gel with his new life, who of all people will suddenly transfer to his squad? Dizzy, the hot little baddie who’s been pursuing Rico since high school. Here’s something I really love about Starship Troopers: in practically every movie in which the leading character is pursued by two love interests, he or she inevitably ends up with the sickeningly wholesome, less attractive option. Not my boy Rico. Soon after his boring girlfriend dumps him via a video call, Rico hooks up with the considerably more exciting Dizzy.

The score by Basil Poledouris is as rousing as anything he’s ever done while the early CGI is somehow much more convincing than most digital effects today. As for the action, it’s exciting, well-paced, and comically bloody as per Verhoeven’s style. If you held a gun to my head and asked me to choose my favorite film of Robocop, Total Recall, and Starship Troopers, I literally couldn’t do it.

I had friends in high school who were even bigger science fiction readers than I. Two of them were dead-set against the idea of a Hollywood adaptation of Robert Heinlein’s source material. There are still critics who assert Verhoeven “ruined the book” by choosing to parody its values (though a lot fewer of them exist today as the general consensus of the film only seems to improve with time). Yes, Isaac Asimov wrote in his memoirs that Heinlein grew more conservative and militaristic with age. Though this is certainly true, Heinlein has suggested he was merely exploring such a society as a possibility, not necessarily promoting it.

Then you have modern SF writers like John Stalzi, who are about as liberal and anti-war as they come, writing military fiction in nearly the same vein as Heinlein. Long before the Sad Puppies (an extreme right-wing group of close-minded assholes who attempted to manipulate the Hugo Awards) I used to enjoy reading science fiction from a wide swath of political and philosophical backgrounds. To like Heinlein’s version and Verhoeven’s isn’t contradictory, but exemplary of what I loved about the brainy genre in the first place. In fact, Joe Halderman’s The Forever War, itself a direct counter-argument to Heinlein’s novel, is among my favorite SF novels of all time.

Though I wish the movie version had gotten the jet packs that Heinlein imagined in the novel, I’m going with Verhoeven’s version all the way.