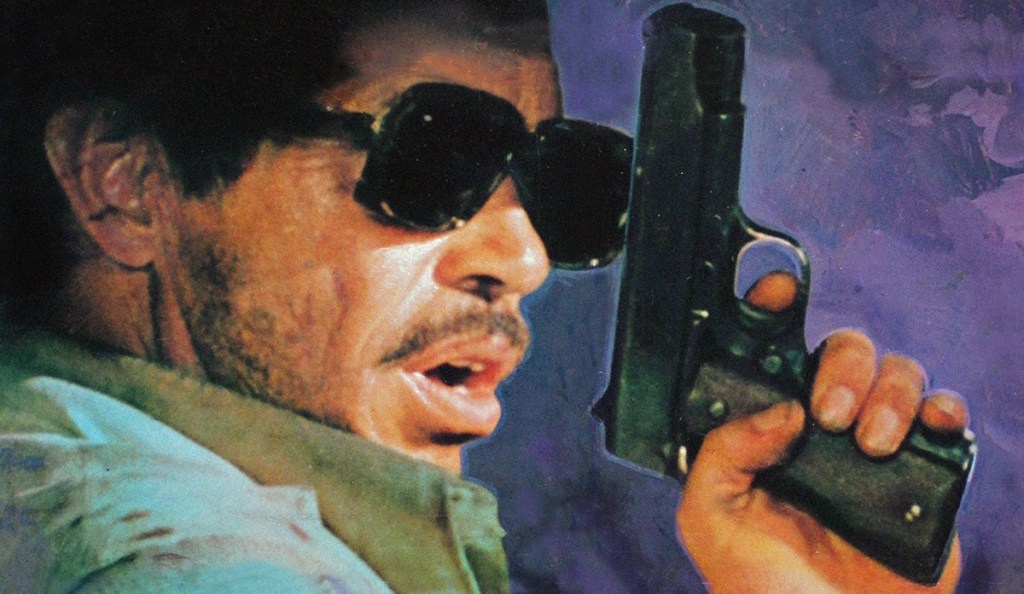

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia isn’t exactly what I had in mind when I started this feature, as the film is entirely lacking in cheese, but it’s got everything else I love about exploitation films: physical conflict, urgent characters, quick women, and tons of senseless violence. On this dreary cold day, I was simply in the mood for Peckinpah.

When the powerful El Jefe (Emilio Fernández) finds out who impregnated his teen daughter, he puts a million dollar bounty on the man’s head (literally). Months later, a couple of the tie-wearing goons end up in a rundown bar in Mexico City, asking questions about Garcia. It’s there they meet the American piano player, Bennie (Warren Oates), who plays stupid. He really doesn’t know where Garcia is, but he suspects his prostitute girlfriend, Elita (Isela Vega), just might.

Not only does Elita know where Garcia is, she’s been planning on leaving Bennie for him. Alfredo Garcia has promised to marry Elita, while Bennie remains reluctant to commit. None of that matters, though, as he comes to realize Garcia’s been dead and buried for a few days now. Armed with this new information, Bennie blows off Elita and seeks out the goons in their hotel room. He agrees to bring them the head of Alfredo Garcia in exchange for ten grand, not knowing the original bounty is much, much higher than that. They agree, giving him a deadline of a few days. They probably don’t have to mention it, but they do anyway: if he runs out on the deal, they’ll have his head.

The night before his journey into the Mexican countryside, Elita visits Bennie in the middle of the night to make up. In the morning, he’s merrily disinfecting crabs with bedside booze. Later, he proposes marriage, but neither he or Elita seem entirely convinced by his newfound enthusiasm. Nonetheless, he brings her along for the trip, which proves to be a mistake when they run into a couple of motorcycle-riding rapists, one of whom is played by Kris Kristofferson. If anything illustrates the stark contrast between the gritty realism of 70s and the almost entirely PG-13 rated present, it’s that music/movie stars used to cameo as despicable thugs. Try to imagine Will Smith or Justin Timberlake doing the same for their careers.

My favorite thing about movies like Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, and crime films in general, is they can take otherwise decent people and put them in soul-altering situations. Bennie, a U.S. Army vet, has no qualms about gunning down criminals, so it’s not taking a man’s life that threatens his soul. No, it’s the moment he digs Garcia up and looms over the corpse with a machete in hand. I believe that’s what plot-heavy screenwriters refer to as an “inciting incident.” Once he crosses that line, there’s no turning back. The descent has begun and the only way out is to continue downward.

Much of the last third of the movie is Bennie justifying his increasingly disturbing decisions to Garcia’s lifeless head, which has begun to draw flies as well as stares from the locals. These monologues, as Bennie continuously unravels, are like something out of an acid western. Warren Oates should’ve been the leading man in a lot more films, which makes Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia more precious. It’s an exhilarating, completely unpretentious joyride with a mad man behind the wheel. And if you’re wondering if “mad man” refers to Peckinpah or the hero, take your pick. It hits hard and kicks ass.